David Henty, a self-proclaimed “King of Forgers,” was eager to discuss his thoughts on Basquiat. An unassuming British man with white hair, tattoos, and a mischievous smile, Henty’s forgeries include works by Basquiat, Caravaggio, and Picasso. His imitations, once covertly sold through art dealers and auction houses, fooled countless buyers. After being exposed by the British media, Henty reinvented himself as a legitimate artist, with his replica works now commanding as much as $70,000. His precise interpretations of Basquiat’s distinctive style have earned him unexpected praise in the art world.

When asked why he chose to forge Basquiat, Henty explained simply, “I liked his style.” He described his process as starting with close copies to get a feel for the artist’s techniques. “I also did a lot of homework—looking at his paintings, exhibitions, auctions, and galleries,” he added.

Why Basquiat?

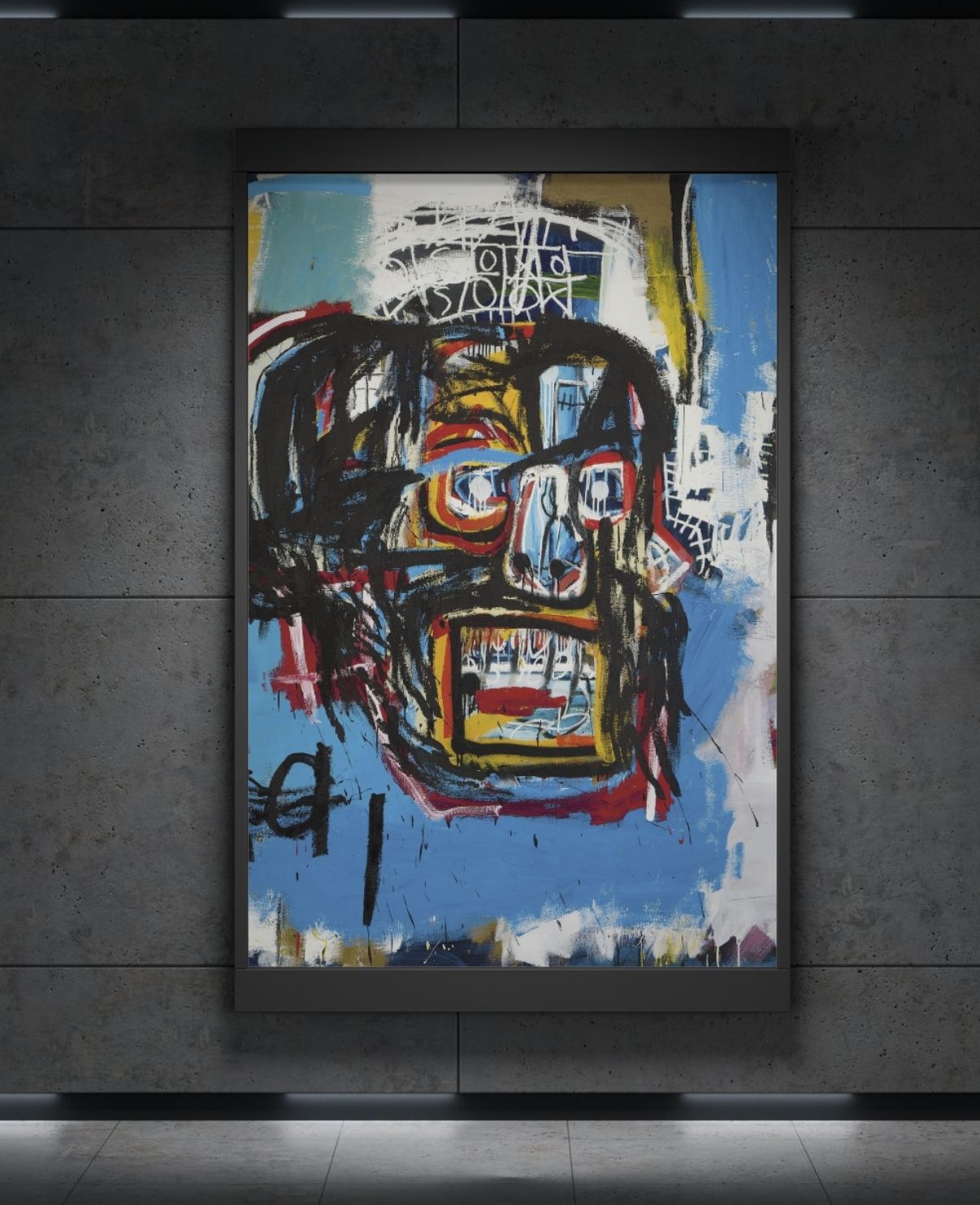

The reasons behind Basquiat’s vulnerability to forgery are rooted in his artistic style, the dynamics of the art market, and the mystique surrounding his persona. His raw, expressive techniques—marked by bold colours, recurring motifs, and cryptic texts—are unmistakable, yet ironically, this recognisable style lends itself to imitation. Forgers, such as Henty, have painstakingly studied his strokes and themes, capitalising on the improvisational nature of his work.

When asked about the challenges of replicating Basquiat’s work, Henty shared, “I don’t find any difficulty in replicating his work or producing new work in his style. It’s just a question of getting in the right mood,” he said. “I like to use triggers—music, documentaries, images. It definitely brings you closer to the artist.”

Of course, a big part of the appeal is the chaotic story of Basquiat himself. His meteoric rise, blending street art aesthetics with gallery prestige, created a cultural and market value that far outpaced the documentation of his work. This left collectors, galleries, and museums navigating a fragmented landscape of provenance and authenticity. The disbanding of the Basquiat Authentication Committee in 2012 deepened that uncertainty, leaving no central authority to verify works attributed to him.

Adding to these challenges is the mythology surrounding Basquiat’s creative process. Known for his bursts of inspiration and unorthodox methods, he left behind few preparatory sketches or detailed records.

Recent Forgery Scandals Involving Basquiat

This vulnerability has led to high-profile forgery scandals involving Basquiat’s name. In 2022, the Orlando Museum of Art made headlines for its Heroes & Monsters exhibition, which featured 25 paintings attributed to Basquiat. These works were seized by the FBI after authenticity concerns surfaced. It was later revealed that Los Angeles auctioneer Michael Barzman had fabricated the paintings, resulting in significant reputational damage for the museum.

Similarly, the Knoedler Gallery in New York faced a major scandal in 2011, when it was discovered that the gallery had sold nearly 40 counterfeit works, including several Basquiats, over a 15-year period. The fraudulent sales earned more than $80 million before the deceit was uncovered, leading to the gallery’s closure and raising broader concerns about the vulnerabilities of the art market.

What Can Museum Professionals Do Differently?

For museums, the risks posed by forgeries—whether attributed to Basquiat or other high-profile artists—are significant. Yet with careful measures, these risks can be mitigated.

First, rigorous provenance research is indispensable. The history of an artwork’s ownership can provide crucial insights into its authenticity. Gaps or inconsistencies in the chain of ownership should be treated as red flags. Museums should require comprehensive documentation, including past sales records, exhibition histories, and certificates of authenticity, before considering acquisitions or loans.

Scientific testing offers another powerful tool in the fight against forgery. Techniques such as carbon dating, pigment analysis, and X-ray fluorescence can reveal whether the materials and methods used are consistent with those of the artist’s era and known practices.

Equally critical is the involvement of independent experts. While museum staff may possess extensive knowledge, enlisting external art historians, curators, or specialists ensures a rigorous, unbiased evaluation. Independent verification can help museums avoid costly mistakes and reinforce public trust in their acquisitions.

Lastly, transparency is essential. Openly addressing doubts about an artwork’s authenticity, rather than concealing them, helps preserve an institution’s credibility. A compelling example of this approach is the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition Concealed Histories: Uncovering the Story of Nazi Looting. In this display, the museum highlighted objects with uncertain provenance, inviting public engagement to resolve gaps in their histories. By acknowledging these uncertainties rather than hiding them, the museum not only maintained its integrity but also reinforced its commitment to ethical stewardship.

Finally, Henty offers an alternative perspective on the role of forgeries in art museums alongside genuine works. “I do believe they have a place,” he asserts. He explains that his process is not unlike an historian, finding the intricacies of an artist’s techniques and creative decisions. What he creates, he suggests, is a form of artistic analysis that deserves recognition. It’s a provocative idea—one that challenges us to view forgeries not merely as acts of deception, but as part of the mystique, the narrative, and analysis of the artists we revere.

Q+A with David Henty

This revealing Q&A features David Henty in conversation with Robert Ossant, a British-born, France-based writer and art historian whose work has appeared in Vogue, The Daily Mail, and numerous prestigious publications. Their exchange offers rare insights into Henty’s process—from his initial attraction to Basquiat’s style to his meticulous research methods.

Why did you choose Basquiat in the first place?

I liked his style.

Did you replicate existing work or create new work inspired by his style? If the latter, how did you choose the subject matter? Did you feel comfortable inhabiting the space of an African American New Yorker?

I copied his paintings closely, as is my way. I like to do a few close copies to get the feel of an artist, and then I felt confident enough to paint in his style. I also did a lot of homework, looking at his paintings, exhibitions, auctions and galleries. One of my best friends is Black and a lover of Basquiat. I had a lot of conversations with him about being Black and how Basquiat painted, reaching back through his ancestors.

What are the practical challenges in replicating his work?

I don’t find any difficulty in replicating his work or producing new work in his style. It’s just a question of getting in the right mood. I like to use triggers—music, documentaries, images, etc.

Do you feel that recreating an artist’s work brings you closer to understanding them? If so, how?

Definitely. I often think it’s like being a historian. I like to find out as much as I can, all the little idiosyncrasies of the artist. I’m looking for little tells, habits, etc.

What can museums do better to protect themselves from acquiring and exhibiting forgeries?

Well, Robert, that would be like a magician revealing his secrets!

I’m interested in the cultural value of a forgery. Are the forgeries part of the story of an artist’s life, and do they deserve to be exhibited alongside the original works? What’s your take?

I do believe they have a place. I’m working on a book about Caravaggio at the moment with my friend, Professor David Forest. We are exploring his working methods, including having a forensic team recreate his palette with nothing synthetic. Together, we aim to make a “new” unseen painting, completely aged and forensically clean. I believe this painting will be something Caravaggio would have painted, had he lived—it’s an extension of his work. The aim is for it to hang alongside other Caravaggio paintings and blend in.

Do you believe forgeries of his work (by you and others) exist in major museum collections and are yet to be uncovered?

The last question I can’t or won’t answer!